Inside Walmart’s Automated Warehouse of the Future

Walmart plans to automate many of its U.S. warehouses, changing what it means to be a warehouse worker. This Brooksville, Fla., warehouse is one of the first.

Walmart plans to automate many of its U.S. warehouses, changing what it means to be a warehouse worker. This Brooksville, Fla., warehouse is one of the first.

As robots work alongside people at Florida facility, some workers gain weight, some like having less physical stress.

Inside a sprawling Walmart in BROOKSVILLE, FLORIDA; green up pointing triangle warehouse here, hundreds of jobs slinging boxes are changing into roles managing robotic arms, conveyor belts and screens.

The central Florida warehouse, surrounded by cow pastures and housing developments, has been one of this county’s largest private employers since it opened in 1991, say local officials. By the end of the year, it will be the first U.S. Walmart warehouse of its kind to use automation to handle most products.

“Welcome to the future,” said José Molina, who has worked in the Brooksville warehouse for 25 years. Three months ago he became an autonomous forklift operator in the facility after years unloading semi trucks the manual way with a pallet jack.

“Now I’m watching the robots unload the truck. I’m behind the robot taking care of the issues,” said Molina, 51. “It’s a big change.” The work is less manual, there is more software knowledge involved, and he has more energy at the end of a shift, he said. Workers who make the leap to automated jobs generally don’t earn higher pay. Walmart’s supply-chain workers earn an average of $25.50 an hour.

Incoming Inbound Products

Traditionally, goods come to the warehouse in trucks, then are manually unloaded with pallet jacks and forklifts. Here, Walmart is testing an autonomous mobile forklift. A single worker can unload multiple trucks at once while monitoring pallet loads for accuracy and damage.

Walmart plans to automate or partially automate many of its hundred-plus U.S. warehouses in the coming years. The shift means Walmart can use fewer people to process more goods and make stocking shelves at stores more efficient. To keep their jobs, many of the company’s tens of thousands of warehouse workers need to retrain for new roles. Some will leave. Warehouses will also need to hire people with new skills, such as technicians.

Large companies such as Walmart and Amazon that rely on massive warehousing networks have worked for years to automate more of their supply chains to increase the volume of packages they can process and reduce labor costs. Because of Walmart’s scale, its plan to make automation standard in more of its supply chain is likely to affect how smaller competitors invest in their own facilities and what a U.S. warehouse job becomes.

“What this technology does for us is increases capacity, increases the accuracy of our loads, increases the speed of the supply chain and lowers cost,” said David Guggina, executive vice president of supply chain for Walmart. It is “also completely reshaping the way that our associates work within the distribution center.”

At the Brooksville warehouse, some workers who made the leap to new automated roles say they like doing less manual labor than in their previous jobs and their typical shift includes more mental stimulation. Workers and supply-chain experts say some prefer the simplicity of the traditional warehouse job.

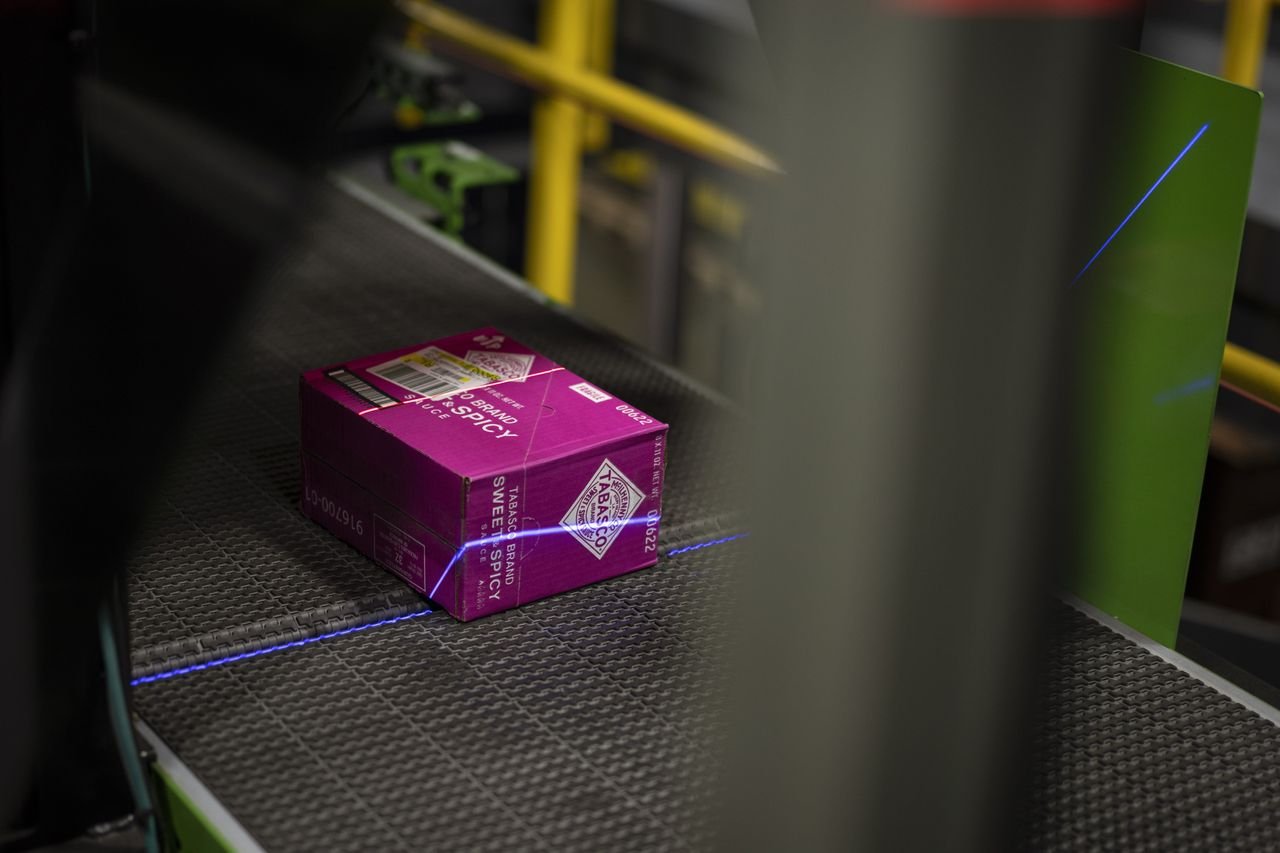

Processing and Sorting

In Brooksville, as sections of robotic arms and screens are gradually installed across the more than 1–million–square-foot facility, some of its roughly 900 workers say they are skeptical about transitioning to new roles that require different skills.

Jose Vargas, 49, who has worked at the Brooksville warehouse for 20 years and transitioned to an automated role about two years ago, said some of his co-workers on the yet-to-be automated side of the building are hesitant to make the leap.

“They are afraid of all this technology,” he said, gesturing to a screen he monitors that is linked to a robotic arm building pallets of goods to ship to stores. He encourages his co-workers to switch. “They still go home and they can’t have fun with their kids or their grandkids because they are tired,” he said.

Kyle Silberger transferred from unloading trucks manually to what Walmart calls an “automated cell operator” about a year ago. “It’s easier physically and harder mentally,” said the 30-year-old who has worked at the warehouse for nine years. “It’s sort of autopilot on the loading dock,” he said, describing his former role.

Some warehouse workers see the physicality of a warehouse job as a benefit, like “this is my gym membership,” said Dan Johnston, chief executive of WorkStep, a firm that helps clients with large hourly workforces track employee sentiment. It doesn’t count Walmart as a client. Physicality, too much or too little, isn’t strongly correlated with job satisfaction or turnover, said Johnston. Advancement, clear job expectations, livable wages and schedules play a bigger role in employee retention, he said.

Outbound Prepping to Ship

Traditionally, workers manually lifted and scanned cases onto conveyor belts or built pallets of goods. This job, which involves the repetitive motion of lifting boxes, is often one of the hardest to fill in a warehouse. Now, robots stack boxes on pallets.

The robot builds the pallet, then wraps it in shrink-wrap for stability during transit. For efficiency, products on pallets are organized by the area of the store where they will be unloaded.

Skepticism and fear of layoffs among workers are common when a warehouse first transitions to automation, said Piyush Sampat, a supply-chain consultant from Deloitte. Many workers are excited about a new challenge, but others leave, he said. Employers automate, in part, to cut labor costs, so losing some workers during the process helps avoid the need for layoffs, said Sampat.

“They don’t want to use the L-word because they don’t want to upset the labor base in that market,” he said.

In Brooksville, Jim Kimbrough, a local banker, courted Walmart to build a distribution center in the community more than three decades ago to provide jobs. Kimbrough, who is now retired, said he visited Walmart founder Sam Walton in Bentonville, Ark., and promised Walton road access and water and sewer services. “About 10 days later, they called and said they were coming to Brooksville,” he said.

The warehouse has been one of the largest private employers and taxpayers in the county ever since, said Valerie Pianta, director of economic development for Hernando County, where the facility is located. Since Walmart started testing automation there in 2017, Walmart executives have told local officials that it wouldn’t need to lay off workers, said Pianta. The facility employs a few hundred fewer workers than it did a few years ago, she said.

“In our Brooksville facility, we’ve significantly improved turnover and job satisfaction in roles that manage the automation, in large part because the physicality of the job is removed,” said a Walmart spokeswoman. Walmart declined to share employment forecasts for the facility.

Walmart’s overall U.S. employee count peaked at around 1.7 million in 2021 after pandemic-related demand for goods rapidly increased the need for workers in stores and warehouses. It fell to 1.6 million last year. Meanwhile, the retailer’s sales have grown quickly since 2020, which means it needs more warehouse capacity.

As Walmart automates, it doesn’t expect its overall U.S. workforce to shrink as it hires for new roles, but it will grow more slowly than in the past, executives said.

At warehouses, managers are emphasizing that the new roles require less manual labor and offer more mental stimulation and potential longevity.

Some of the jobs offer a pathway to higher-paying automation roles such as systems operators, said the Walmart spokeswoman.

Workers receive around six weeks of training when they transition, learning about software, fixing issues as they arise and how to track inventory as it is passed between robots.

Melinda Clemens, who has worked in the Brooksville warehouse for three years, initially turned down an automated version of her job. “I was skeptical. It looked very intimidating,” said the 30-year-old. As time went on and she started aching after shifts lifting boxes, it sounded more appealing, said Clemens.

“I started thinking maybe in the long run it might be better to give my body a break.”

Source Story by Sarah Nassauer at Sarah.Nassauer@wsj.com and Dave Cole at david.cole@wsj.com